Data Should Drive COVID-19 Mitigation Strategies in Lower- and Middle-Income Countries

The current World Health Organization’s guidelines call for the public focus on handwashing, social distancing, communication with medical providers, and staying informed to help mitigate the spread of COVID-19. However, such guidance may be more aspirational than actionable for millions at risk of exposure to the virus in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) as revealed by recent Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). DHS data from 2014 onward from more than 50 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America highlight the very different contexts for daily living in LMICs. These realities must be considered when developing country or context-specific strategies for reducing COVID-19 transmission.

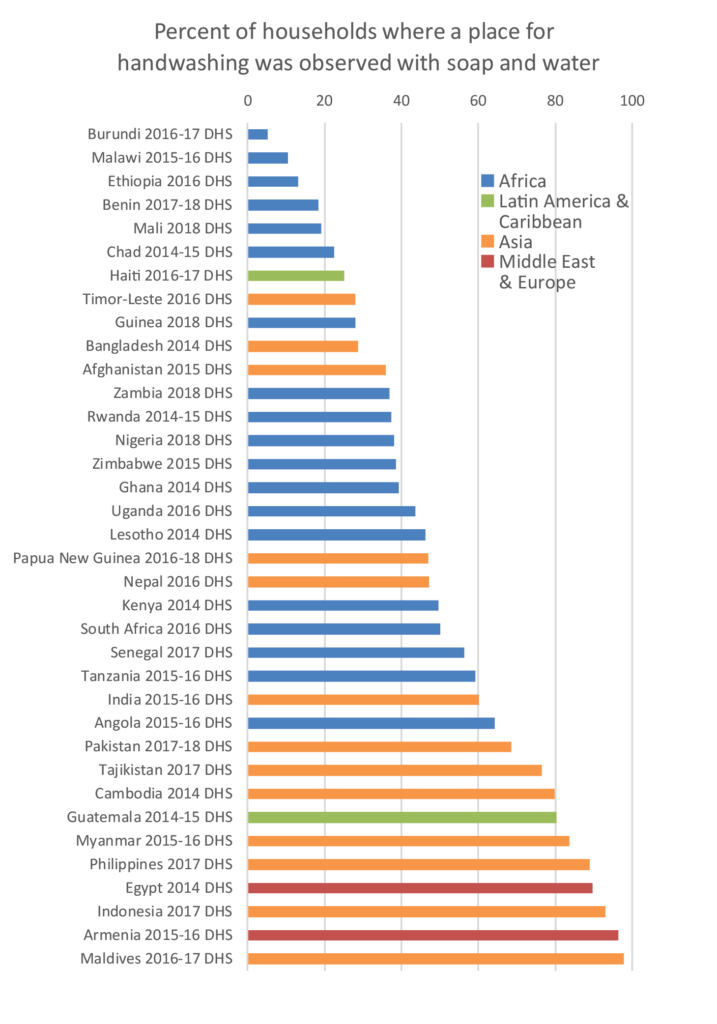

Handwashing:

The basics required for handwashing (soap and water) are taken for granted by many but are not readily available for millions of people. In Burundi (2016-17 DHS), only 5% of households were observed to have soap and water for handwashing (among those where handwashing places were observed). Soap and water were present in fewer than 20% of households in Malawi, Ethiopia, Benin, and Mali (see chart). A location for handwashing with soap and water was found in fewer than half of households in 21 out of 36 recent surveys for which The DHS Program has this information.

Household Size and Sleeping Arrangements:

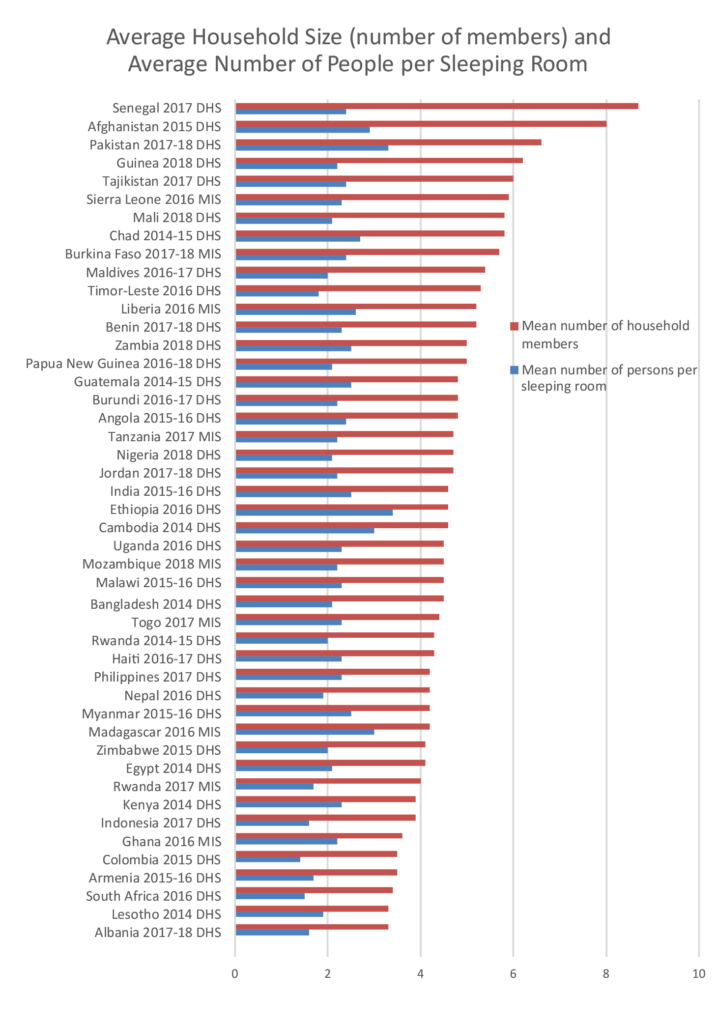

Messaging about social distancing in the current pandemic focuses on staying home and reducing contact with people. In LMICs, self-quarantining to individual households and nuclear families may not be a particularly useful concept.

Households in Sierra Leone, Tajikistan, Guinea, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Senegal are the largest, with six or more members on average. The ability to distance from sick or vulnerable family members within the household is crucial, but in many households sleeping quarters are crowded. Households in Pakistan, Madagascar, Ethiopia, and Cambodia have the highest average of people per sleeping room, at three or more.

Household Age Structure:

A recent article in the Hindustan Times pointed out that multi-generational households in India might be a risk factor for coronavirus transmission to the elderly. The 2015-16 India National Family Health Survey (India’s DHS) reported that 4 in 10 Indian households are non-nuclear families, many of which are multi-generational. This type of family structure makes social distancing, especially for the elderly, very challenging. When younger children go to school, or working-age adults go to work, they return home to multi-generational families in which the elderly are particularly vulnerable to coronavirus. While the proportion of population age 65+ in DHS countries is not large, there are some key things to note, particularly within the context of multigenerational households. In recent surveys, on average, about 5% of the population is 65+, but in countries like India (6.6%) and Indonesia (6.2%), these seemingly small percentages correspond to many millions of people due to population size.

Explore these data in STATcompiler

The DHS Program’s STATcompiler allows users to create custom tables, charts, and maps from 1000s of indicators across 90 countries.

Just this week, the STATcompiler has been updated to include new indicators to help contextualize the COVID-19 crisis in DHS countries, and two “COVID19” tags have been added to help users identify these indicators. Explore data on handwashing, sanitation, household size, sleeping arrangements, access to media, spousal violence, and more. Other relevant DHS indicators on household age structure, access to internet and cell phones, and tobacco use will be added in the coming weeks.

Select indicators and explore two new COVID tags in STATcompiler.com.

Access to Information:

Health emergencies necessitate that urgent information be shared with the public in a timely manner. And yet large portions of the global population live without regular access to mass media. More than half of women age 15-49 in Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Benin, Timor-Leste, Niger, Malawi, Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, Papua New Guinea, Ethiopia, and Chad report that they do not have weekly access to information via radio, television, or newspaper.

In 30 out of 47 recent DHS surveys, at least 75% of households owned at least one mobile telephone. Still, ownership is lower in rural areas, and still uncommon in some countries; in Madagascar, for example, only one-third of households owned a mobile phone in 2016. Internet access, however, is very low across DHS countries. In Nigeria, only 16% of women and 35% of men age 15-49 used the internet in the past year (2018 NDHS). In Zambia, use was even lower, at 12% of women and 26% of men (2018 ZDHS).

Additional Considerations: Domestic Violence, Tobacco Use, and Access to Basic Health Services

And then there are potential secondary risk factors. How does cigarette smoking affect vulnerability? How will families cope with the stresses of a pandemic and the interpersonal conflicts exacerbated in quarantine settings? Will women and children continue to get the general health services they need, such as vaccinations, antenatal and delivery care, family planning, and nutritional support? These questions are important in all settings, but especially in those that are still in the process of building systems to support accessible, quality health care services. In Nigeria, for example, fewer than one-third of children age 12-23 months have received all 8 basic vaccinations, only about 40% of births are delivered in a health facility, and 19% of women have an unmet need for family planning.

Averaging across countries with data on spousal violence shows that 1 out of 4 women report physical, sexual, or emotional violence committed by their husband or partner within the last 12 months, and 36% report ever having faced such violence in their lifetime. These data suggest that social distancing may expose a significant proportion of already vulnerable women to a heightened risk of violence as women are forced to spend even more time with their abusers than usual and their access to sources of help is further limited by the pandemic.

There are countless other factors that are likely affecting COVID-19 transmission throughout the world. Urbanization, and slum environments in particular, are breeding grounds for contagion. In LMICs, millions of people migrate to city-centers for employment and are now migrating home to rural areas seeking safe-haven. These and myriad other factors can be explored in DHS datasets and final reports.

Conclusion:

Pandemics require data-driven decisions. While it is one unique virus that has spanned the globe, individual nations, communities, cultures, and families all face it within their own contexts. We can’t collect DHS household data during a pandemic. But we owe it to families in DHS countries to use the information already collected to better inform decisions to provide recommendations that resonate in their settings and to safeguard their already fragile health infrastructure.

Thanks for this interesting facts. I wonder why you have not included Sri Lanka in this graph?

Great question. This blog post only considers data from 2014 onward. Additionally, The DHS Program was not involved in the completion of the most recent demographic and health surveys conducted in Sri Lanka. You can contact the Sri Lanka Department of Census and Statistics for Sri Lanka DHS data.

Thanks for this timely and informative article. It has given me good ideas for the analysis of my country data.

Thank you for this timely information! This sparked a good idea for research!

Amazing Blog with lots of Interesting inspiration. I will definitely come back here more than once. He will share his Blog on Facebook. Regards, Decoratorium.

Very interesting data. Will read more definitely! Thank you